Revision 1da950d066d18291411c9549d9c4e2b9fbe9d859 authored by Skye Wanderman-Milne on 06 December 2019, 05:38:59 UTC, committed by Skye Wanderman-Milne on 06 December 2019, 05:38:59 UTC

1 parent 7a154f7

README.md

<div align="center">

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/google/jax/master/images/jax_logo_250px.png" alt="logo"></img>

</div>

# JAX: Autograd and XLA [](https://travis-ci.org/google/jax)

[**Reference docs**](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/)

| [**Install guide**](#installation)

| [**Quickstart**](#quickstart-colab-in-the-cloud)

JAX is [Autograd](https://github.com/hips/autograd) and

[XLA](https://www.tensorflow.org/xla),

brought together for high-performance machine learning research.

With its updated version of [Autograd](https://github.com/hips/autograd),

JAX can automatically differentiate native

Python and NumPy functions. It can differentiate through loops, branches,

recursion, and closures, and it can take derivatives of derivatives of

derivatives. It supports reverse-mode differentiation (a.k.a. backpropagation)

via [`grad`](#automatic-differentiation-with-grad) as well as forward-mode differentiation,

and the two can be composed arbitrarily to any order.

What’s new is that JAX uses

[XLA](https://www.tensorflow.org/xla)

to compile and run your NumPy programs on GPUs and TPUs. Compilation happens

under the hood by default, with library calls getting just-in-time compiled and

executed. But JAX also lets you just-in-time compile your own Python functions

into XLA-optimized kernels using a one-function API,

[`jit`](#compilation-with-jit). Compilation and automatic differentiation can be

composed arbitrarily, so you can express sophisticated algorithms and get

maximal performance without leaving Python.

Dig a little deeper, and you'll see that JAX is really an extensible system for

[composable function transformations](#transformations). Both

[`grad`](#automatic-differentiation-with-grad) and [`jit`](#compilation-with-jit)

are instances of such transformations. Another is [`vmap`](#auto-vectorization-with-vmap)

for automatic vectorization, with more to come.

This is a research project, not an official Google product. Expect bugs and

[sharp edges](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/Common_Gotchas_in_JAX.html).

Please help by trying it out, [reporting

bugs](https://github.com/google/jax/issues), and letting us know what you

think!

```python

import jax.numpy as np

from jax import grad, jit, vmap

def predict(params, inputs):

for W, b in params:

outputs = np.dot(inputs, W) + b

inputs = np.tanh(outputs)

return outputs

def logprob_fun(params, inputs, targets):

preds = predict(params, inputs)

return np.sum((preds - targets)**2)

grad_fun = jit(grad(logprob_fun)) # compiled gradient evaluation function

perex_grads = jit(vmap(grad_fun, in_axes=(None, 0, 0))) # fast per-example grads

```

JAX started as a research project by [Matt Johnson](https://github.com/mattjj),

[Roy Frostig](https://github.com/froystig), [Dougal

Maclaurin](https://github.com/dougalm), and [Chris

Leary](https://github.com/learyg), and is now developed [in the

open](https://github.com/google/jax) by a growing number of

[contributors](#contributors).

### Contents

* [Quickstart: Colab in the Cloud](#quickstart-colab-in-the-cloud)

* [Installation](#installation)

* [Reference documentation](#reference-documentation)

* [A brief tour](#a-brief-tour)

* [What's supported](#whats-supported)

* [Transformations](#transformations)

* [Random numbers are different](#random-numbers-are-different)

* [Mini-libraries](#mini-libraries)

* [How it works](#how-it-works)

* [Current gotchas](#current-gotchas)

* [Citing JAX](#citing-jax)

## Quickstart: Colab in the Cloud

Jump right in using a notebook in your browser, connected to a Google Cloud GPU. Here are some starter notebooks:

- [The basics: NumPy on accelerators, `grad` for differentiation, `jit` for compilation, and `vmap` for vectorization](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/quickstart.html)

- [Training a Simple Neural Network, with PyTorch Data Loading](https://colab.research.google.com/github/google/jax/blob/master/docs/notebooks/Neural_Network_and_Data_Loading.ipynb)

- [Training a Simple Neural Network, with TensorFlow Dataset Data Loading](https://colab.research.google.com/github/google/jax/blob/master/docs/notebooks/neural_network_with_tfds_data.ipynb)

And for a deeper dive into JAX:

- [Common gotchas and sharp edges](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/Common_Gotchas_in_JAX.html)

- [The Autodiff Cookbook, Part 1: easy and powerful automatic differentiation in JAX](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/autodiff_cookbook.html)

- [Directly using XLA in Python](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/XLA_in_Python.html)

- [How JAX primitives work](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/How_JAX_primitives_work.html)

- [MAML Tutorial with JAX](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/maml.html)

- [Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of Data Distribution in JAX](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/score_matching.html).

## Installation

JAX is written in pure Python, but it depends on XLA, which needs to be compiled

and installed as the `jaxlib` package. Use the following instructions to

install a binary package with `pip`, or to build JAX from source.

We support installing or building `jaxlib` on Linux (Ubuntu 16.04 or later) and

macOS (10.12 or later) platforms, but not yet Windows. We're not currently

working on Windows support, but contributions are welcome

(see [#438](https://github.com/google/jax/issues/438)). Some users have reported

success with building a CPU-only `jaxlib` from source using the Windows Subsytem

for Linux.

### pip installation

To install a CPU-only version, which might be useful for doing local

development on a laptop, you can run

```bash

pip install --upgrade pip

pip install --upgrade jax jaxlib # CPU-only version

```

On Linux, it is often necessary to first update `pip` to a version that supports

`manylinux2010` wheels.

If you want to install JAX with both CPU and GPU support, using existing CUDA

and CUDNN7 installations on your machine (for example, preinstalled on your

cloud VM), you can run

```bash

# install jaxlib

PYTHON_VERSION=cp37 # alternatives: cp27, cp35, cp36, cp37

CUDA_VERSION=cuda92 # alternatives: cuda90, cuda92, cuda100, cuda101

PLATFORM=linux_x86_64 # alternatives: linux_x86_64

BASE_URL='https://storage.googleapis.com/jax-releases'

pip install --upgrade $BASE_URL/$CUDA_VERSION/jaxlib-0.1.36-$PYTHON_VERSION-none-$PLATFORM.whl

pip install --upgrade jax # install jax

```

The library package name must correspond to the version of the existing CUDA

installation you want to use, with `cuda101` for CUDA 10.1, `cuda100` for CUDA

10.0, `cuda92` for CUDA 9.2, and `cuda90` for CUDA 9.0. To find your CUDA and

CUDNN versions, you can run commands like these, depending on your CUDNN install

path:

```bash

nvcc --version

grep CUDNN_MAJOR -A 2 /usr/local/cuda/include/cudnn.h # might need different path

```

The Python version must match your Python interpreter. There are prebuilt wheels

for Python 2.7, 3.5, 3.6, and 3.7; for anything else, you must build from

source.

Please let us know on [the issue tracker](https://github.com/google/jax/issues)

if you run into any errors or problems with the prebuilt wheels.

### Building JAX from source

See [Building JAX from source](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/developer.html#building-from-source).

## Reference documentation

For details about the JAX API, see the

[reference documentation](https://jax.readthedocs.io/).

## Developer documentation

For getting started as a JAX developer, see the

[developer documentation](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/developer.html).

## A brief tour

```python

In [1]: import jax.numpy as np

In [2]: from jax import random

In [3]: key = random.PRNGKey(0)

In [4]: x = random.normal(key, (5000, 5000))

In [5]: print(np.dot(x, x.T) / 2) # fast!

[[ 2.52727051e+03 8.15895557e+00 -8.53276134e-01 ..., # ...

In [6]: print(np.dot(x, x.T) / 2) # even faster!

# JIT-compiled code is cached and reused in the 2nd call

[[ 2.52727051e+03 8.15895557e+00 -8.53276134e-01 ..., # ...

```

What’s happening behind-the-scenes is that JAX is using XLA to just-in-time

(JIT) compile and execute these individual operations on the GPU. First the

`random.normal` call is compiled and the array referred to by `x` is generated

on the GPU. Next, each function called on `x` (namely `transpose`, `dot`, and

`divide`) is individually JIT-compiled and executed, each keeping its results on

the device.

It’s only when a value needs to be printed, plotted, saved, or passed into a raw

NumPy function that a read-only copy of the value is brought back to the host as

an ndarray and cached. The second call to `dot` is faster because the

JIT-compiled code is cached and reused, saving the compilation time.

The fun really starts when you use `grad` for automatic differentiation and

`jit` to compile your own functions end-to-end. Here’s a more complete toy

example:

```python

from jax import grad, jit

import jax.numpy as np

def sigmoid(x):

return 0.5 * (np.tanh(x / 2.) + 1)

# Outputs probability of a label being true according to logistic model.

def logistic_predictions(weights, inputs):

return sigmoid(np.dot(inputs, weights))

# Training loss is the negative log-likelihood of the training labels.

def loss(weights, inputs, targets):

preds = logistic_predictions(weights, inputs)

label_logprobs = np.log(preds) * targets + np.log(1 - preds) * (1 - targets)

return -np.sum(label_logprobs)

# Build a toy dataset.

inputs = np.array([[0.52, 1.12, 0.77],

[0.88, -1.08, 0.15],

[0.52, 0.06, -1.30],

[0.74, -2.49, 1.39]])

targets = np.array([True, True, False, True])

# Define a compiled function that returns gradients of the training loss

training_gradient_fun = jit(grad(loss))

# Optimize weights using gradient descent.

weights = np.array([0.0, 0.0, 0.0])

print("Initial loss: {:0.2f}".format(loss(weights, inputs, targets)))

for i in range(100):

weights -= 0.1 * training_gradient_fun(weights, inputs, targets)

print("Trained loss: {:0.2f}".format(loss(weights, inputs, targets)))

```

To see more, check out the [quickstart

notebook](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/quickstart.html),

a [simple MNIST classifier

example](https://github.com/google/jax/blob/master/examples/mnist_classifier.py)

and the rest of the [JAX

examples](https://github.com/google/jax/blob/master/examples/).

## What's supported

If you’re using JAX just as an accelerator-backed NumPy, without using `grad` or

`jit` in your code, then in principle there are no constraints, though some

NumPy functions haven’t been implemented yet. A list of supported functions can

be found in the [reference documentation](https://jax.readthedocs.io/).

Generally using `np.dot(A, B)` is

better than `A.dot(B)` because the former gives us more opportunities to run the

computation on the device. NumPy also does a lot of work to cast any array-like

function arguments to arrays, as in `np.sum([x, y])`, while `jax.numpy`

typically requires explicit casting of array arguments, like

`np.sum(np.array([x, y]))`.

For automatic differentiation with `grad`, JAX has the same restrictions

as [Autograd](https://github.com/hips/autograd). Specifically, differentiation

works with indexing (`x = A[i, j, :]`) but not indexed assignment (`A[i, j] =

x`) or indexed in-place updating (`A[i] += b`) (use

[`jax.ops.index_update`](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/_autosummary/jax.ops.index_update.html#jax.ops.index_update)

or

[`jax.ops.index_add`](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/_autosummary/jax.ops.index_add.html#jax.ops.index_add)

instead). You can use lists, tuples, and

dicts freely: JAX doesn't even see them. Using `np.dot(A, B)` rather than

`A.dot(B)` is required for automatic differentiation when `A` is a raw ndarray.

For compiling your own functions with `jit` there are a few more requirements.

Because `jit` aims to specialize Python functions only on shapes and dtypes

during tracing, rather than on concrete values, Python control flow that depends

on concrete values won’t be able to execute and will instead raise an error. If

you want compiled control flow, use structured control flow primitives like

`lax.cond` and `lax.while_loop`. Some indexing features, like slice-based

indexing, e.g. `A[i:i+5]` for argument-dependent `i`, or boolean-based indexing,

e.g. `A[bool_ind]` for argument-dependent `bool_ind`, produce abstract values of

unknown shape and are thus unsupported in `jit` functions.

In general, JAX is intended to be used with a functional style of Python

programming. Functions passed to transformations like `grad` and `jit` are

expected to be free of side-effects. You can write print statements for

debugging but they may only be executed once if they're under a `jit` decorator.

> TLDR **Do use**

>

> * Functional programming

> * [Many](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/jax.numpy.html) of NumPy’s

> functions (help us add more!)

> * [Some](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/jax.scipy.html) SciPy functions

> * Indexing and slicing of arrays like `x = A[[5, 1, 7], :, 2:4]`

> * Explicit array creation from lists like `A = np.array([x, y])`

>

> **Don’t use**

>

> * Assignment into arrays like `A[0, 0] = x` (use

> [`jax.ops.index_update`](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/_autosummary/jax.ops.index_update.html#jax.ops.index_update)

> instead)

> * Implicit casting to arrays like `np.sum([x, y])` (use `np.sum(np.array([x,

> y])` instead)

> * `A.dot(B)` method syntax for functions of more than one argument (use

> `np.dot(A, B)` instead)

> * Side-effects like mutation of arguments or mutation of global variables

> * The `out` argument of NumPy functions

> * Dtype casting like `np.float64(x)` (use `x.astype('float64')` or

> `x.astype(np.float64)` instead).

>

> **For jit functions, also don’t use**

>

> * Control flow based on dynamic values `if x > 0: ...`. Control flow based

> on shapes is fine: `if x.shape[0] > 2: ...` and `for subarr in array`.

> * Slicing `A[i:i+5]` for dynamic index `i` (use `lax.dynamic_slice` instead)

> or boolean indexing `A[bool_ind]` for traced values `bool_ind`.

You should get loud errors if your code violates any of these.

## Transformations

At its core, JAX is an extensible system for transforming numerical functions.

We currently expose three important transformations: `grad`, `jit`, and `vmap`.

### Automatic differentiation with grad

JAX has roughly the same API as [Autograd](https://github.com/hips/autograd).

The most popular function is `grad` for reverse-mode gradients:

```python

from jax import grad

import jax.numpy as np

def tanh(x): # Define a function

y = np.exp(-2.0 * x)

return (1.0 - y) / (1.0 + y)

grad_tanh = grad(tanh) # Obtain its gradient function

print(grad_tanh(1.0)) # Evaluate it at x = 1.0

# prints 0.41997434161402603

```

You can differentiate to any order with `grad`.

For more advanced autodiff, you can use `jax.vjp` for reverse-mode

vector-Jacobian products and `jax.jvp` for forward-mode Jacobian-vector

products. The two can be composed arbitrarily with one another, and with other

JAX transformations. Here's one way to compose

those to make a function that efficiently computes full Hessian matrices:

```python

from jax import jit, jacfwd, jacrev

def hessian(fun):

return jit(jacfwd(jacrev(fun)))

```

As with Autograd, you're free to use differentiation with Python control

structures:

```python

def abs_val(x):

if x > 0:

return x

else:

return -x

abs_val_grad = grad(abs_val)

print(abs_val_grad(1.0)) # prints 1.0

print(abs_val_grad(-1.0)) # prints -1.0 (abs_val is re-evaluated)

```

### Compilation with jit

You can use XLA to compile your functions end-to-end with `jit`, used either as

an `@jit` decorator or as a higher-order function.

```python

import jax.numpy as np

from jax import jit

def slow_f(x):

# Element-wise ops see a large benefit from fusion

return x * x + x * 2.0

x = np.ones((5000, 5000))

fast_f = jit(slow_f)

%timeit -n10 -r3 fast_f(x) # ~ 4.5 ms / loop on Titan X

%timeit -n10 -r3 slow_f(x) # ~ 14.5 ms / loop (also on GPU via JAX)

```

You can mix `jit` and `grad` and any other JAX transformation however you like.

### Auto-vectorization with vmap

`vmap` is the vectorizing map.

It has the familiar semantics of mapping a function along array axes, but

instead of keeping the loop on the outside, it pushes the loop down into a

function’s primitive operations for better performance.

Using `vmap` can save you from having to carry around batch dimensions in your

code. For example, consider this simple *unbatched* neural network prediction

function:

```python

def predict(params, input_vec):

assert input_vec.ndim == 1

for W, b in params:

output_vec = np.dot(W, input_vec) + b # `input_vec` on the right-hand side!

input_vec = np.tanh(output_vec)

return output_vec

```

We often instead write `np.dot(inputs, W)` to allow for a batch dimension on the

left side of `inputs`, but we’ve written this particular prediction function to

apply only to single input vectors. If we wanted to apply this function to a

batch of inputs at once, semantically we could just write

```python

from functools import partial

predictions = np.stack(list(map(partial(predict, params), input_batch)))

```

But pushing one example through the network at a time would be slow! It’s better

to vectorize the computation, so that at every layer we’re doing matrix-matrix

multiplies rather than matrix-vector multiplies.

The `vmap` function does that transformation for us. That is, if we write

```python

from jax import vmap

predictions = vmap(partial(predict, params))(input_batch)

# or, alternatively

predictions = vmap(predict, in_axes=(None, 0))(params, input_batch)

```

then the `vmap` function will push the outer loop inside the function, and our

machine will end up executing matrix-matrix multiplications exactly as if we’d

done the batching by hand.

It’s easy enough to manually batch a simple neural network without `vmap`, but

in other cases manual vectorization can be impractical or impossible. Take the

problem of efficiently computing per-example gradients: that is, for a fixed set

of parameters, we want to compute the gradient of our loss function evaluated

separately at each example in a batch. With `vmap`, it’s easy:

```python

per_example_gradients = vmap(partial(grad(loss), params))(inputs, targets)

```

Of course, `vmap` can be arbitrarily composed with `jit`, `grad`, and any other

JAX transformation! We use `vmap` with both forward- and reverse-mode automatic

differentiation for fast Jacobian and Hessian matrix calculations in

`jax.jacfwd`, `jax.jacrev`, and `jax.hessian`.

## Random numbers are different

JAX needs a [functional pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) system](design_notes/prng.md) to provide

reproducible results invariant to compilation boundaries and backends, while

also maximizing performance by enabling vectorized generation and

parallelization across random calls. The `numpy.random` library doesn’t have

those properties. The `jax.random` library meets those needs: it’s functionally

pure, but it doesn’t require you to pass stateful random objects back out of

every function.

The `jax.random` library uses

[count-based PRNGs](http://www.thesalmons.org/john/random123/papers/random123sc11.pdf)

and a functional array-oriented

[splitting model](http://publications.lib.chalmers.se/records/fulltext/183348/local_183348.pdf).

To generate random values, you call a function like `jax.random.normal` and give

it a PRNG key:

```python

import jax.random as random

key = random.PRNGKey(0)

print(random.normal(key, shape=(3,))) # [ 1.81608593 -0.48262325 0.33988902]

```

If we make the same call again with the same key, we get the same values:

```python

print(random.normal(key, shape=(3,))) # [ 1.81608593 -0.48262325 0.33988902]

```

The key never gets updated. So how do we get fresh random values? We use

`jax.random.split` to create new keys from existing ones. A common pattern is to

split off a new key for every function call that needs random values:

```python

key = random.PRNGKey(0)

key, subkey = random.split(key)

print(random.normal(subkey, shape=(3,))) # [ 1.1378783 -1.22095478 -0.59153646]

key, subkey = random.split(key)

print(random.normal(subkey, shape=(3,))) # [-0.06607265 0.16676566 1.17800343]

```

By splitting the PRNG key, not only do we avoid having to thread random states

back out of every function call, but also we can generate multiple random arrays

in parallel because we can avoid unnecessary sequential dependencies.

There's a gotcha here, which is that it's easy to unintentionally reuse a key

without splitting. We intend to add a check for this (a sort of dynamic linear

typing) but for now it's something to be careful about.

For more detailed information on the design and the reasoning behind it, see the

[PRNG design doc](design_notes/prng.md).

## Mini-libraries

JAX provides some small, experimental libraries for machine learning. These

libraries are in part about providing tools and in part about serving as

examples for how to build such libraries using JAX. Each one is only a few

hundred lines of code, so take a look inside and adapt them as you need!

### Neural-net building with Stax

**Stax** is a functional neural network building library. The basic idea is that

a single layer or an entire network can be modeled as an `(init_fun, apply_fun)`

pair. The `init_fun` is used to initialize network parameters and the

`apply_fun` takes parameters and inputs to produce outputs. There are

constructor functions for common basic pairs, like `Conv` and `Relu`, and these

pairs can be composed in series using `stax.serial` or in parallel using

`stax.parallel`.

Here’s an example:

```python

import jax.numpy as np

from jax import random

from jax.experimental import stax

from jax.experimental.stax import Conv, Dense, MaxPool, Relu, Flatten, LogSoftmax

# Use stax to set up network initialization and evaluation functions

net_init, net_apply = stax.serial(

Conv(32, (3, 3), padding='SAME'), Relu,

Conv(64, (3, 3), padding='SAME'), Relu,

MaxPool((2, 2)), Flatten,

Dense(128), Relu,

Dense(10), LogSoftmax,

)

# Initialize parameters, not committing to a batch shape

rng = random.PRNGKey(0)

in_shape = (-1, 28, 28, 1)

out_shape, net_params = net_init(rng, in_shape)

# Apply network to dummy inputs

inputs = np.zeros((128, 28, 28, 1))

predictions = net_apply(net_params, inputs)

```

### First-order optimization

JAX has a minimal optimization library focused on stochastic first-order

optimizers. Every optimizer is modeled as an `(init_fun, update_fun,

get_params)` triple of functions. The `init_fun` is used to initialize the

optimizer state, which could include things like momentum variables, and the

`update_fun` accepts a gradient and an optimizer state to produce a new

optimizer state. The `get_params` function extracts the current iterate (i.e.

the current parameters) from the optimizer state. The parameters being optimized

can be ndarrays or arbitrarily-nested list/tuple/dict structures, so you can

store your parameters however you’d like.

Here’s an example, using `jit` to compile the whole update end-to-end:

```python

from jax.experimental import optimizers

from jax import jit, grad

# Define a simple squared-error loss

def loss(params, batch):

inputs, targets = batch

predictions = net_apply(params, inputs)

return np.sum((predictions - targets)**2)

# Use optimizers to set optimizer initialization and update functions

opt_init, opt_update, get_params = optimizers.momentum(step_size=1e-3, mass=0.9)

# Define a compiled update step

@jit

def step(i, opt_state, batch):

params = get_params(opt_state)

g = grad(loss)(params, batch)

return opt_update(i, g, opt_state)

# Dummy input data stream

data_generator = ((np.zeros((128, 28, 28, 1)), np.zeros((128, 10)))

for _ in range(10))

# Optimize parameters in a loop

opt_state = opt_init(net_params)

for i in range(10):

opt_state = step(i, opt_state, next(data_generator))

net_params = get_params(opt_state)

```

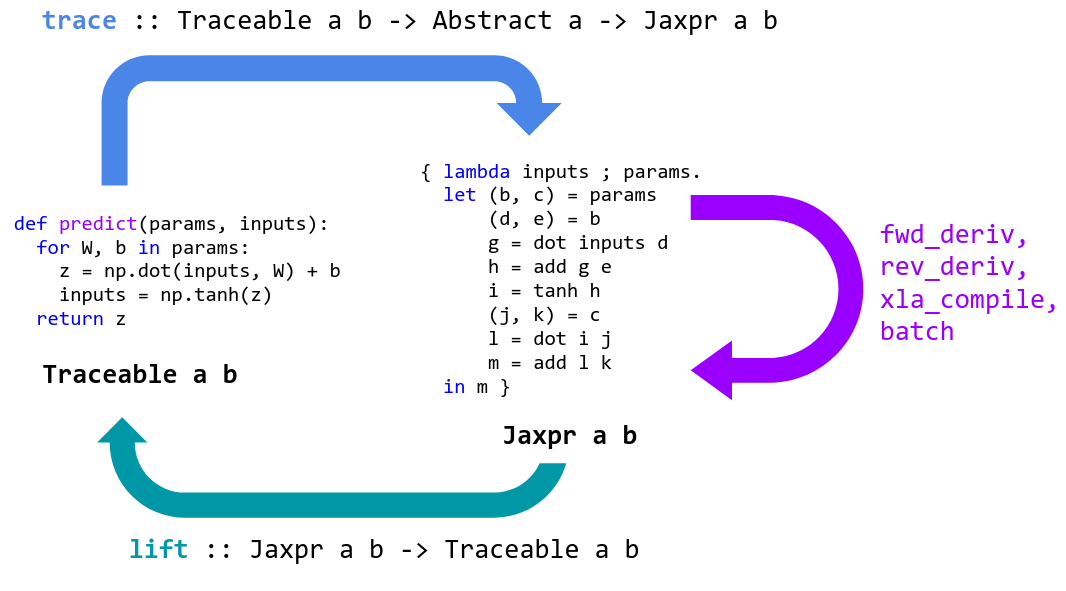

## How it works

Programming in machine learning is about expressing and transforming functions.

Transformations include automatic differentiation, compilation for accelerators,

and automatic batching. High-level languages like Python are great for

expressing functions, but usually all we can do with them is apply them. We lose

access to their internal structure which would let us perform transformations.

JAX is a tool for specializing and translating high-level Python+NumPy functions

into a representation that can be transformed and then lifted back into a Python

function.

JAX specializes Python functions by tracing. Tracing a function means monitoring

all the basic operations that are applied to its input to produce its output,

and recording these operations and the data-flow between them in a directed

acyclic graph (DAG). To perform tracing, JAX wraps primitive operations, like

basic numerical kernels, so that when they’re called they add themselves to a

list of operations performed along with their inputs and outputs. To keep track

of how data flows between these primitives, values being tracked are wrapped in

instances of the `Tracer` class.

When a Python function is provided to `grad` or `jit`, it’s wrapped for tracing

and returned. When the wrapped function is called, we abstract the concrete

arguments provided into instances of the `AbstractValue` class, box them for

tracing in instances of the `Tracer` class, and call the function on them.

Abstract arguments represent sets of possible values rather than specific

values: for example, `jit` abstracts ndarray arguments to abstract values that

represent all ndarrays with the same shape and dtype. In contrast, `grad`

abstracts ndarray arguments to represent an infinitesimal neighborhood of the

underlying

value. By tracing the Python function on these abstract values, we ensure that

it’s specialized enough so that it’s tractable to transform, and that it’s still

general enough so that the transformed result is useful, and possibly reusable.

These transformed functions are then lifted back into Python callables in a way

that allows them to be traced and transformed again as needed.

The primitive functions that JAX traces are mostly in 1:1 correspondence with

[XLA HLO](https://www.tensorflow.org/xla/operation_semantics) and are defined

in [lax.py](https://github.com/google/jax/blob/master/jax/lax/lax.py). This 1:1

correspondence makes most of the translations to XLA essentially trivial, and

ensures we only have a small set of primitives to cover for other

transformations like automatic differentiation. The [`jax.numpy`

layer](https://github.com/google/jax/blob/master/jax/numpy/) is written in pure

Python simply by expressing NumPy functions in terms of the LAX functions (and

other NumPy functions we’ve already written). That makes `jax.numpy` easy to

extend.

When you use `jax.numpy`, the underlying LAX primitives are `jit`-compiled

behind the scenes, allowing you to write unrestricted Python+Numpy code while

still executing each primitive operation on an accelerator.

But JAX can do more: instead of just compiling and dispatching to a fixed set of

individual primitives, you can use `jit` on larger and larger functions to be

end-to-end compiled and optimized. For example, instead of just compiling and

dispatching a convolution op, you can compile a whole network, or a whole

gradient evaluation and optimizer update step.

The tradeoff is that `jit` functions have to satisfy some additional

specialization requirements: since we want to compile traces that are

specialized on shapes and dtypes, but not specialized all the way to concrete

values, the Python code under a `jit` decorator must be applicable to abstract

values. If we try to evaluate `x > 0` on an abstract `x`, the result is an

abstract value representing the set `{True, False}`, and so a Python branch like

`if x > 0` will raise an error: it doesn’t know which way to go!

See [What’s supported](#whats-supported) for more

information about `jit` requirements.

The good news about this tradeoff is that `jit` is opt-in: JAX libraries use

`jit` on individual operations and functions behind the scenes, allowing you to

write unrestricted Python+Numpy and still make use of a hardware accelerator.

But when you want to maximize performance, you can often use `jit` in your own

code to compile and end-to-end optimize much bigger functions.

## Current gotchas

For a survey of current gotchas, with examples and explanations, we highly

recommend reading the [Gotchas Notebook](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/Common_Gotchas_in_JAX.html).

Some stand-out gotchas that might surprise NumPy users:

1. JAX enforces single-precision (32-bit, e.g. `float32`) values by default, and

to enable double-precision (64-bit, e.g. `float64`) one needs to set the

`jax_enable_x64` variable **at startup** (or set the environment variable

`JAX_ENABLE_X64=True`, see [the Gotchas Notebook](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/Common_Gotchas_in_JAX.html#scrollTo=Double-(64bit)-precision))

2. Some of NumPy's dtype promotion semantics involving a mix of Python scalars

and NumPy types aren't preserved, namely `np.add(1, np.array([2],

np.float32)).dtype` is `float64` rather than `float32`.

3. In-place mutation of arrays isn't supported, though [there is an

alternative](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/jax.ops.html). Generally

JAX requires functional code.

4. PRNGs are different and can be awkward, though for [good

reasons](https://github.com/google/jax/blob/master/design_notes/prng.md), and

non-reuse (linearity) is not yet checked.

See [the notebook](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/Common_Gotchas_in_JAX.html) for much more information.

## Citing JAX

To cite this repository:

```

@software{jax2018github,

author = {James Bradbury and Roy Frostig and Peter Hawkins and Matthew James Johnson and Chris Leary and Dougal Maclaurin and Skye Wanderman-Milne},

title = {{JAX}: composable transformations of {P}ython+{N}um{P}y programs},

url = {http://github.com/google/jax},

version = {0.1.46},

year = {2018},

}

```

In the above bibtex entry, names are in alphabetical order, the version number

is intended to be that from [jax/version.py](../blob/master/jax/version.py), and

the year corresponds to the project's open-source release.

A nascent version of JAX, supporting only automatic differentiation and

compilation to XLA, was described in a [paper that appeared at SysML

2018](https://www.sysml.cc/doc/2018/146.pdf). We're currently working on

covering JAX's ideas and capabilities in a more comprehensive and up-to-date

paper.

## Contributors

So far, JAX includes lots of help and [contributions](https://github.com/google/jax/graphs/contributors). In addition to the code contributions reflected on GitHub, JAX has benefitted substantially from the advice of

[Jamie Townsend](https://github.com/j-towns),

[Peter Hawkins](https://github.com/hawkinsp),

[Jonathan Ragan-Kelley](https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~jrk/),

[Alex Wiltschko](http://github.com/alexbw),

George Dahl,

[Stephan Hoyer](http://stephanhoyer.com/),

Sam Schoenholz,

[Eli Bendersky](https://github.com/eliben),

Zak Stone,

[Alexey Radul](https://github.com/axch),

Michael Isard,

Skye Wanderman-Milne,

and many others.

Computing file changes ...